Fairs + Projects

2026

Melbourne Art Fair 2026

Jacqueline Stojanović

2025

Melbourne Art Fair 2025

Sebastian Temple

2024

RENDER pt. II

Shelley Lasica

RENDER

Shelley Lasica

Thin Green Mist, Small Grey Stain

Beau Emmett

Melbourne Art Fair 2024

Renee Cosgrave

2023

Spring1883 at The Hotel Windsor

Amalia Lindo, Sam Martin

Aotearoa Art Fair 2023

Eliza Hutchison

2022

Aotearoa Art Fair 2022

Stephen Bram, Renee Cosgrave, Anna Fiedler, Guy Grabowsky, Sam Martin, Rose Nolan, Stephanie Pile, Allan Rand, Jacqueline Stojanović, Masato Takasaka, Audrey Tan, Sarah Ujmaia, Tim Wagg

2021

Spring1883 at ALPHA60 Chapter House

Guy Grabowsky, Jordan Halsall, Amalia Lindo

The Melbourne Art Fair 2026

Jacqueline Stojanović

19.02.2026 - 22.02.2026

Click here to request digital catalogue

Jacqueline Stojanović

19.02.2026 - 22.02.2026

Click here to request digital catalogue

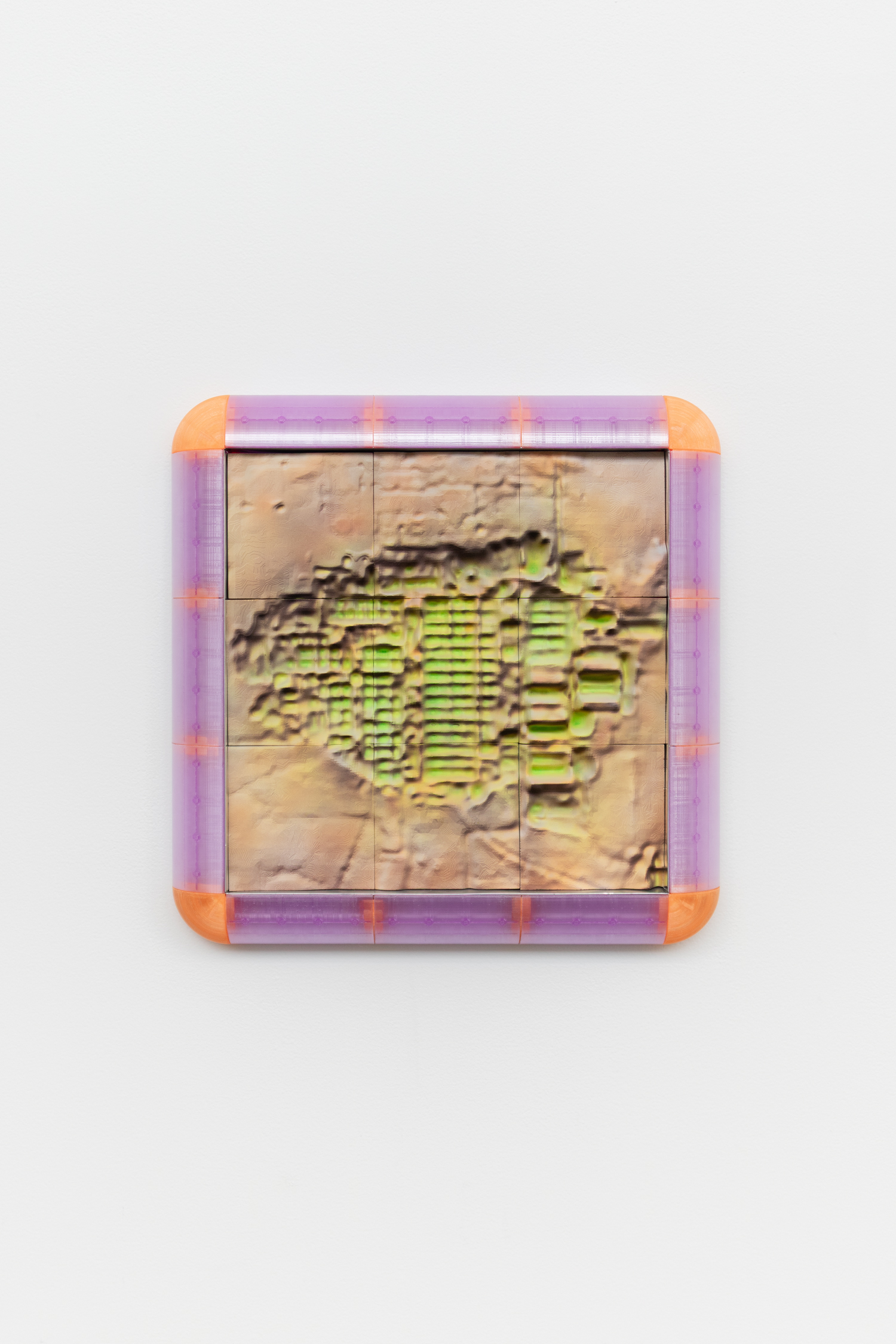

Haydens is pleased to present a selection of new artworks by Jacqueline Stojanović for The Melbourne Art Fair 2026. The focus of this presentation are two bodies of work: contemporary textiles and woodblock mosaics. The textiles, meticulously wound onto steel grids in Stojanović’s signature style, hark back to her ongoing series of Grids, while her mosaics break the mould of rigid geometry, referencing stars and celestial forms.

Stojanović’s textiles, titled Field drawings, feature a vibrant array of hues, the deep blues and greens of fermented indigo, bright yellows and ochres of mistletoe, pinks of both wattlebark and safflower, and the dull chartreuse of wild cherry ballart. Many of these materials have been scavenged from Stojanović’s local surroundings or grown in her garden. Others have more sentimental meaning, such as the dark yellows, browns, and greys drawn out of pomegranates from her mother’s tree. The inimitability of these colours is the result of an alchemical reaction of metallic mordants, plant tannins, and the fibres themselves, revealing a secret world that exists in our living environment.

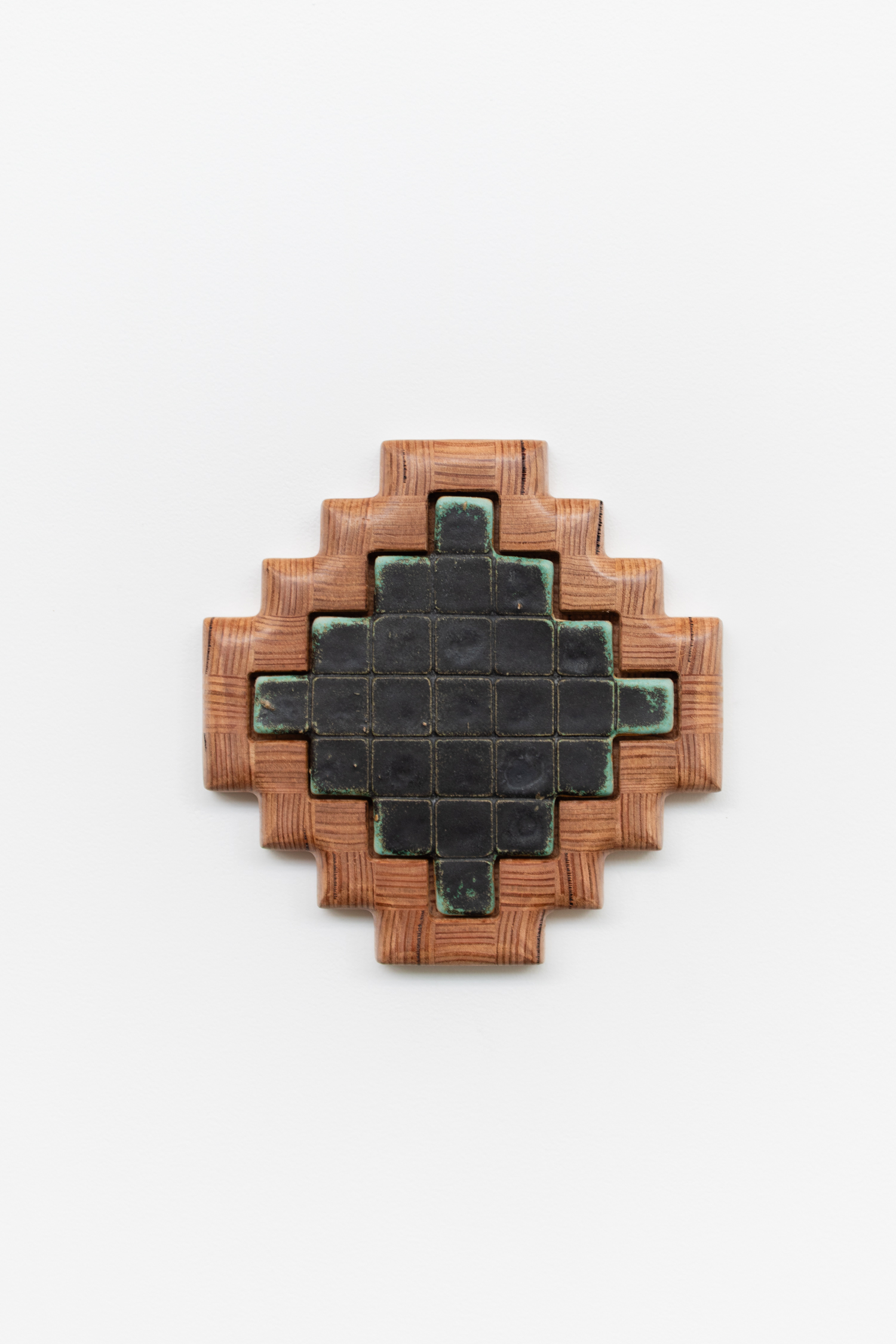

Accompanying her Field drawings are a series of woodblock mosaics created while in Serbia. The inspiration for the mosaics can be drawn back to Stojanović’s experience of ancient tile works of Byzantium, still prevalent in the Orthodox churches of Belgrade. Sourcing earth, mineral, and plant-based pigments, like those used in eastern iconography, Stojanović utilises traditional painting techniques and hand-mixed pigments and mediums to broaden her spectrum of colour, furthering a connection between her culture and the natural world.

In contrast to nature, the mosaics and grid’s formal geometries reference iconic brutalist social housing blocks of her biographical homeland of former-Yugoslavia. The tension between wilderness and the rigidity of modern industrialisation is central to both these bodies of work, and her apt use of a subdued palette memorialises the connection to her diaspora.

Pairing these two expanded series highlights Stojanović’s interest in the relationship between colour and culture. The use of natural dyes and pigments extends her investigation into the essence and significance of colour, grounded in her culture’s spiritual beliefs of artistic depiction – void of figuration and using only that which comes from the natural world.

Stojanović’s textiles, titled Field drawings, feature a vibrant array of hues, the deep blues and greens of fermented indigo, bright yellows and ochres of mistletoe, pinks of both wattlebark and safflower, and the dull chartreuse of wild cherry ballart. Many of these materials have been scavenged from Stojanović’s local surroundings or grown in her garden. Others have more sentimental meaning, such as the dark yellows, browns, and greys drawn out of pomegranates from her mother’s tree. The inimitability of these colours is the result of an alchemical reaction of metallic mordants, plant tannins, and the fibres themselves, revealing a secret world that exists in our living environment.

Accompanying her Field drawings are a series of woodblock mosaics created while in Serbia. The inspiration for the mosaics can be drawn back to Stojanović’s experience of ancient tile works of Byzantium, still prevalent in the Orthodox churches of Belgrade. Sourcing earth, mineral, and plant-based pigments, like those used in eastern iconography, Stojanović utilises traditional painting techniques and hand-mixed pigments and mediums to broaden her spectrum of colour, furthering a connection between her culture and the natural world.

In contrast to nature, the mosaics and grid’s formal geometries reference iconic brutalist social housing blocks of her biographical homeland of former-Yugoslavia. The tension between wilderness and the rigidity of modern industrialisation is central to both these bodies of work, and her apt use of a subdued palette memorialises the connection to her diaspora.

Pairing these two expanded series highlights Stojanović’s interest in the relationship between colour and culture. The use of natural dyes and pigments extends her investigation into the essence and significance of colour, grounded in her culture’s spiritual beliefs of artistic depiction – void of figuration and using only that which comes from the natural world.

Shelley Lasica

with contributions from:

Indiana Coole, Louella May Hogan, Claire Leske, Caroline Meaden, Kate Meakin, Andrew Wilson.

Thursday 29th of January

from 7 pm

1/10-12 Moreland Road

Brunswick East 3057

This is the sixth part of RENDER, a series that will be displayed in varying formats confounding the performance of choreography with its rendering. Shelley Lasica with contributions from Indiana Coole, Louella May Hogan, Claire Leske, Caroline Meaden, Kate Meakin, Andrew Wilson.

Assistance though Callie’s Berlin Residency 2023/2024 and The Australian Ballet.

Assistance though Callie’s Berlin Residency 2023/2024 and The Australian Ballet.

Spring1883 Art Fair

at The Hotel Windsor

Renee Cosgrave, Guy Grabowsky, Amalia Lindo, Jordan Mitchell-Fletcher, Nicholas Smith, Jacqueline Stojanović, Sebastian Temple, Tim Wagg

14.08.2025 - 16.08.2025

at The Hotel Windsor

Renee Cosgrave, Guy Grabowsky, Amalia Lindo, Jordan Mitchell-Fletcher, Nicholas Smith, Jacqueline Stojanović, Sebastian Temple, Tim Wagg

14.08.2025 - 16.08.2025

Haydens is pleased to be participating in the 9th edition of the Spring1883 Art Fair at The Hotel Windsor.

Featuring works by all of our represented artists gathered together for the first time, Renee Cosgrave, Guy Grabowsky, Amalia Lindo, Jordan Mitchell-Fletcher, Nicholas Smith, Jacqueline Stojanović, Sebastian Temple, and Tim Wagg.

Join us from the 14th until the 16th of August to celebrate Australasia’s premier gallery-led art fair.

Featuring works by all of our represented artists gathered together for the first time, Renee Cosgrave, Guy Grabowsky, Amalia Lindo, Jordan Mitchell-Fletcher, Nicholas Smith, Jacqueline Stojanović, Sebastian Temple, and Tim Wagg.

Join us from the 14th until the 16th of August to celebrate Australasia’s premier gallery-led art fair.

The Melbourne Art Fair 2025

Sebastian Temple

20.02.2025 - 23.02.2025

Sebastian Temple

20.02.2025 - 23.02.2025

Haydens is pleased to present a new body of work by

Sebastian Temple for The Melbourne Art Fair 2025. This

presentation brings together a diverse range of artworks, connecting ceramics,

paintings, and wooden sculptures through Temple’s expanded drawing practice.

Embracing uncertainty and slow, intuitive processes, he integrates scavenged

materials, natural decay, and shared experiences, creating works that exist in

a state of constant flux.

Drawing serves as the foundation of Temple’s multidisciplinary approach. “I think of most of my work as an expanded drawing,” he explains. “It exists in a constant state of becoming, shifting between function and transformation.” His works—ceramic vessels, furniture-like constructions, and reconfigured sculptures—often emerge from deconstructed and repurposed materials. Rooted in resourcefulness, his practice reflects a philosophy of adaptation, making do with what is readily available.

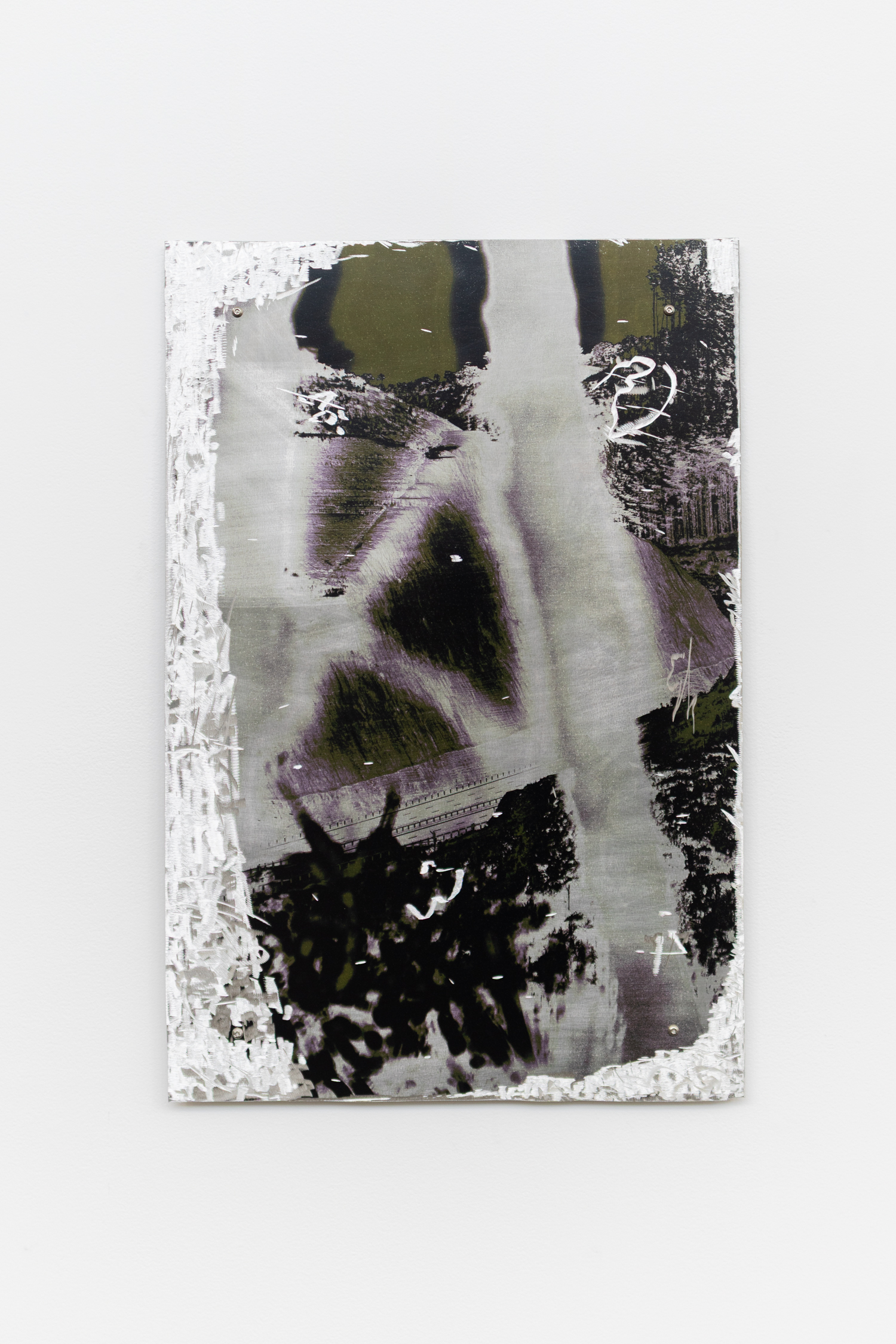

A highlight of Temple’s Melbourne Art Fair presentation is a large, mural scaled painting that has travelled with him for seven years, absorbing and reflecting the different environments he has inhabited. From working in a suburban garage in Perth to adapting to a variety of living and studio conditions, the painting encapsulates layers of lived experience.

His sculptural works similarly embrace transformation. Using found wood, scavenged materials, and ceramics, these objects oscillate between function and art—at times serving as stools, stands, or containers, and at others resisting utility entirely. “I like the tension between function, purpose, and artwork,” Temple says. “It allows for shifts in meaning, where something utilitarian suddenly becomes precious, or vice versa.”

Through his evolving interplay of drawing, sculpture, and functional objects, Temple challenges material hierarchies and invites us to reconsider the potential of discarded materials. His work offers a thoughtful reflection on sustainability, collaboration, and transformation—an especially relevant pursuit in today’s shifting environmental and economic landscape.

The Melbourne Art Fair runs from the 20th to the 23rd of February at The Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre. Visit us at Booth I3 to view Sebastian Temple’s latest works.

Sebastian TempleDrawing serves as the foundation of Temple’s multidisciplinary approach. “I think of most of my work as an expanded drawing,” he explains. “It exists in a constant state of becoming, shifting between function and transformation.” His works—ceramic vessels, furniture-like constructions, and reconfigured sculptures—often emerge from deconstructed and repurposed materials. Rooted in resourcefulness, his practice reflects a philosophy of adaptation, making do with what is readily available.

A highlight of Temple’s Melbourne Art Fair presentation is a large, mural scaled painting that has travelled with him for seven years, absorbing and reflecting the different environments he has inhabited. From working in a suburban garage in Perth to adapting to a variety of living and studio conditions, the painting encapsulates layers of lived experience.

His sculptural works similarly embrace transformation. Using found wood, scavenged materials, and ceramics, these objects oscillate between function and art—at times serving as stools, stands, or containers, and at others resisting utility entirely. “I like the tension between function, purpose, and artwork,” Temple says. “It allows for shifts in meaning, where something utilitarian suddenly becomes precious, or vice versa.”

Through his evolving interplay of drawing, sculpture, and functional objects, Temple challenges material hierarchies and invites us to reconsider the potential of discarded materials. His work offers a thoughtful reflection on sustainability, collaboration, and transformation—an especially relevant pursuit in today’s shifting environmental and economic landscape.

The Melbourne Art Fair runs from the 20th to the 23rd of February at The Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre. Visit us at Booth I3 to view Sebastian Temple’s latest works.

in conversation with

Hayden Stuart

*

Hayden

As we look at the work you have presented for The Melbourne Art Fair 2025, we can see that you use many different mediums to explore your ideas. Artworks take shape as ceramic vessels, paintings, sculptures, or furniture that is sometimes functional, sometimes not. This is all linked together through drawing. How do you decide where to start and in what medium to express your ideas?

I use drawings to facilitate other works, like an idea that goes a bit rampant, and I consider most of my work as an expanded drawing. I’m interested in the phrasing, the platform, the moment in between possible states of constant becoming, particularly the grey area between rubbish and a finished work. I find an artwork that has been recycled endearing – As a result, I often start with deconstructing and reconfiguring old works, beginning by picking apart the dregs of a past project (which can take up a lot of physical space so it’s also a very practical choice), or my decision about what medium to work in could stem from a discarded drawing I am surprised by. I have a certain distrust of my initial ideas, so I try to find an alternative way to enable their transformation - sometimes through making a functional object, practical problem solving, or collaboration.

H

What inspires you to make work? Do you draw inspiration from art historical references, or is your practice a process of understanding the world around you?

Perhaps it is not so much about understanding the world around me, but how to use things gained or learned from historical references, as well as lived experiences and concepts relating to the way in which I would like to live. How to use what is in front of you, or to see what is abundant, as well as how to share and collaborate.

H

When we take a closer look at your drawings, they slowly start to unravel themselves. From the swirling, chaotic compositions appear figures, objects, and written phrases such as “desperate studio production”, “health and safety guidelines”, “phone repair guides”, “plans”, and “pottering”. There seems to be a banality to these notes, as though they describe part of your everyday experience. Do these drawings embody your experiences? Or do your drawings fulfill a direct, practical function like a note or list?

S

I think a lot of the drawings do start out very functional, containing things such as lists, plans, calendars, procrastinations, lounging, day to day things and gestures in my studio. These things get caught up as material, and it is often mundane and embarrassing. It reveals the hand, something fleeting and hazy, simultaneously a plan and a finished work. My tools, systems, the physical spaces and environments, the practicalities and limitations of my workspace, and the anxiety of to-do lists, embody experiences but also change into symbols in the translations between states and materials. I never really see things as finished, just working in the slowest, long winded and impractical way. Pencil on paper is so traditional and yet enables daydreaming and slippages of meaning so efficiently.

H

Functionality seems to be something that your works also touch on. From your drawings which become practical records of your life, to makeshift stools made from scavenged wood in your local area, and then the ceramic vessels you refer to as “Giant Bins”. What do you believe is the purpose or function of art in relation to your practice? Does it exist to tell a story, or fill a certain functional role in our lives, or a combination of these ideas?

S

I do aspire to make multi-functional objects and works, using them in practical ways - like studio furniture, bins, stands for new works or a studio on wheels. But also, to find a moment where it falls away. The function becomes unknown, and the purpose has changed, or is transforming. I quite like this tension, it helps with these slippages of meaning which can result in surprising and erratic outcomes, and a story emerges of interactions between materials, feeling and practice. I also find it funny to have something utilitarian such as a bin or a stool and to make it into a precious art object. I have worked in a few furniture workshops, and they always have the most beautifully crafted tables that are used as workbenches, or a frilly, ornate cabinet to hold the sandpaper. With the ceramics I have been working on recently, they circle back to become more like drawings, and the function is less and less obvious.

H

In your last solo exhibition Pinching Machine at Haydens, there was a strong relationship between your work and your garden where you live in the Yarra Valley. The wooden structure you created in the gallery, alongside the mass of hand-carved furniture, had been subject to the elements, and featured worn, patinated timber scavenged locally, as well as left-over pieces from previous sculptures. You have previously described this as a collaborative process with nature, and in fact a lot of your work seems to respond to your surrounding conditions. Are there other ways in which nature influences your work? Or can you tell us more about your relationship to the garden, and how you work with nature?

S

My work always is very connected to the environment it is created in. When I lived in the western suburbs of Melbourne which is surrounded by a lot of industrial areas, I was always amazed at the amount of discarded timber that was available to collect. Now moving to the valley, I am also amazed at the quantity of wood that the forest generates. I amassed a huge collection of materials that have tended to spill into the outdoor environment. My studio had to move outside, and I was working amongst the bugs and with the elements.

My sculptures started to get eaten, rot and patina, like a collaboration. It felt like a loss of control and an opportunity for exchange and uncertainty. Spending time in the garden I started to appreciate the circular and symbiotic relationships: so much activity breaking things down for a new season, recycling, periods of slowness and frantic activity. I have become obsessed with composting; at home I have 3 compost bins!

My sculptures started to get eaten, rot and patina, like a collaboration. It felt like a loss of control and an opportunity for exchange and uncertainty. Spending time in the garden I started to appreciate the circular and symbiotic relationships: so much activity breaking things down for a new season, recycling, periods of slowness and frantic activity. I have become obsessed with composting; at home I have 3 compost bins!

H

In your most recent group exhibition triple power of plants at Goolugatup Heathcote, Perth, you also collaborated with Audrey and Jess Tan to create a large sprawling sculpture, and several sculptural pieces scattered around the room. Collaboration appears to be an important part of your practice; do you believe this challenges the concept of artistic ‘genius’ or the solitary figure of the artist?

S

Working in collaboration with other artists totally debunks the myth of the genius artist. I love collaboration because what the project manifests as is always very unexpected, surprising, and humorous. I find it’s also a good time to explore doing something that everybody hasn’t done before or has only a vague understanding of how to do it, like with triple power the first thing we decided to do was to try and make paper from blended up weeds and the work kind of snowballed from that tangent.

It’s more exciting to think with more than one brain, which allows the time and space for skill sharing, taking the longest route, risk taking, arguing, mixing business with pleasure, collecting, exchanging ideas, not-knowing and un-learning set ways of working, thinking and being.

It’s more exciting to think with more than one brain, which allows the time and space for skill sharing, taking the longest route, risk taking, arguing, mixing business with pleasure, collecting, exchanging ideas, not-knowing and un-learning set ways of working, thinking and being.

H

The works from triple power of plants included materials such as “pulped eucalyptus from Kate and Pete’s backyard, pulped oxalis from Hickey street backyard, soapstone dust, pulped food packaging, salt, sea grass from port beach, butterfly pea flower, phycocyanin spirulina, dried dragon fruit pulp, assorted leaf tannins, hole punched vape packaging, corn husk and baci wrappers.” Using unorthodox materials like this has strong relations to art historical movements such as Arte Povera from the 60’s – 70’s in Italy. Materials such as soil, rags, and twigs challenged values of the commercialised contemporary gallery system in a time of economic instability. Do you believe it is important to develop artistic strategies such as scavenging and recycling in relation to our current economic and political situation?

SI think so, even environmentally now as well, it is very relevant to this current climate, and we often do it out of necessity. We weren’t successful in receiving funding for a grant we applied for, so looking in the backyard of our residency dwelling for material seemed like a very logical step. Scavenging and walking, hard rubbish, looking slowly, and seeing potential in the scraps from things we consume. The three of us share these methodologies that tend to draw new attention to old and discarded works and materials, repurposing, and constant restless transformation.

H

You have been working on a large-scale painting for your presentation at The Melbourne Art Fair. What challenges did you experience with this change of scale and medium, and were there any unexpected results?

S

I have been carrying this painting around since 2018, bringing it with me whenever I’ve moved house and studios. In a way, it turned into a piece of furniture for creating my ideal studio setup, like having the perfect table or a nice variety of crates. It was always the first thing set up my studio - it became a surface to bounce ideas off. I recently carried it to Perth in my suitcase, taking it with me to various suburban houses I stayed at during my trip. Different people and houses offer different spaces to work - at one house I was painting at a table in the formal dining room, trying to be careful about paint drips and stains, being surrounded by conversation, air conditioning, and music. When I relocated to another house halfway through my stay, I began working in the garage with the painting hung on the wall, navigating the frottage of the bricks, grease stains on the ground, listening to the backyard chickens muttering, and leaving for a swim when I couldn’t deal with the mosquitos and heat any longer. I like when a painting contains all this experience and information held within it.

January 2025